The real cost of the reclamation boom

By Chantal Eco

As new land is gained from the sea, coastal communities lose their homes and livelihood.

BANAGO, BACOLOD CITY – Clad in a DIY wetsuit of a long-sleeve shirt, spandex pants, and a black bonnet, Alberto Bucado, 56, dives into the cold water of Guimaras Strait northwest of Negros Island. Bubbles soon emerge around bamboo poles pinned into the waterbed, signifying his position. Half an hour later, the fisher resurfaces with a net full of mussels or “green shells” as the locals literally call them.

Bucado’s family meets him on the shore. His sons help him clean the haul. His wife Annie, 46, sells them for ₱80 a kilogram on the sidewalks of Libertad market in downtown Bacolod.

They earn about ₱1,300 for an entire day’s work, barely enough to sustain the needs of their family of seven.

This has been the Bucados’ livelihood for two decades. But they may soon lose their only source of income when hundreds of hectares of land is reclaimed from the coast of Banago and nearby villages where at least 6,000 fisherfolk live.

In 2022, a company reported to be owned by the family of a city councilor started dumping sand and rocks in one of five reclamation sites. The activities were halted but only temporarily.

Bucado points into the sea where their mussel farm and saprahan (fish traps) are located. “Sa masami ara lang dira ang buoy nga may ara sang marka kung sa diin ila iula ang balas (There used to be a buoy there with a sign to mark up to where they will dump sand),” he said.

The mystery of reclamation projects

Uncertainty about the future has gripped many fisherfolk across the country as plans to create land from the sea advance in secret. Altermidya has spent the last six months identifying and gathering details of 239 reclamation projects, including those in Bacolod, where commercial, industrial, and transportation facilities will soon rise.

The government has no centralized list of reclamation authorities and Altermidya identified many projects not listed by the Philippines Reclamation Authority. Even though the PRA is the primary regulatory body for all reclamation works, they do not include infrastructure projects led by other agencies that also involve reclamation. To come up with a comprehensive list, Altermidya compiled records obtained from the PRA and the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), another regulatory body that issues clearances. Certain projects by the Department of Works and Highways, like causeways, were also identified as they require significant reclamation. There could be more that we were not able to identify.

Timelapse of satellite images from 2022 to 2024 showing the 390-hectare reclamation project by the Pasay City local government and SM Prime Holdings, located just across from the SM Mall of Asia complex.

These projects are touted by the government and private investors as creators of new jobs and revenue streams while the specific details of projects are withheld. But in areas where reclamation has begun, coastal communities already suffer the consequences, from eviction and depleted fish catch and environmentalists sound the alarm about the dangers of creating land out of nothing.

In the face of public backlash, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. ordered an indefinite suspension of 22 major land reclamation projects in Manila Bay in 2022 yet our research shows that approvals continue to go through. The PRA confirmed that applications and approvals of reclamation works are still being done on a case-to-case basis, often behind closed doors. Fisherfolk and environmental groups now question whether regulators properly oversee these projects.

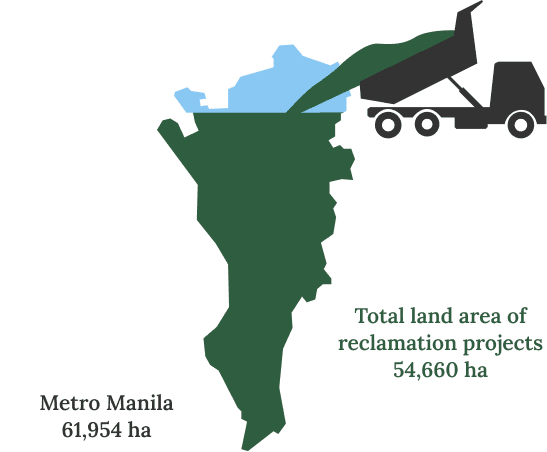

Projects silently spread to cover land the size of Metro Manila

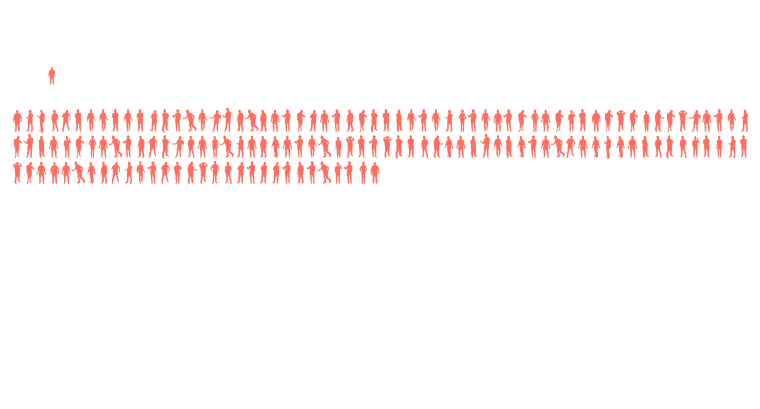

We counted a total of at least 239 projects under PRA and various other agencies. If combined, these projects would create at least 54,660 hectares of artificial land close to the size of Metro Manila. They span the entire country, from Cagayan to South Cotabato.

As of February 2024, PRA has only listed 54 reclamation projects, 17 of these already have permits, while 6 are already being implemented. The other 185 have either been removed from PRA’s list due ‘lack of interest’, are still under application, or are ongoing but are not listed as reclamation projects. At least 157 approved causeway projects by the DPWH were also identified where 28 have already been completed.

The largest ones are mostly located along Manila Bay, in and around the country’s metropolis. Many are slated for shopping malls, casinos, and condominiums as well as industrial complexes such as manufacturing, processing, and warehouses.

Some projects are intended for connectivity like expressways, railways, ports, and airports. At least four projects – the New Manila International Airport, LRT-1 Extension Project, Sangley Airport, and Caticlan Airport – are part of “Build Better More,” Marcos Jr.’s infrastructure development program which expanded the Duterte administration’s “Build! Build! Build!” program. In fact, all four projects were approved during Duterte’s term.

If all reclamation projects are added up, they would be almost the same size as Metro Manila

Big business and political interest, not public works and welfare, drive reclamation projects

According to our analysis, most reclamation projects are either entirely or partially business ventures by big corporations.

While some funding for projects will either come from the annual budget, official development assistance or foreign loans like the LRT-1 Extension Project, most are public-private partnerships like the ongoing New Manila International Airport in Bulacan, a project of Ramon Ang’s San Miguel Corp. (SMC).

👆

Cavitex Holdings Inc., a subsidiary of Manuel ‘Manny’ V. Pangilinan’s Metro Pacific Investments Corp. and R-II Builders Inc. of port tycoon Reghis Romero II are also involved in a combined 4,400 hectares of reclamation, but their investment amounts remain undisclosed.

Some of these corporations have been involved in displacing communities to pave way for their projects. For instance, SMC has already displaced hundreds of fisherfolks for the construction of the New Manila International Airport in Bulacan; SM was responsible for cutting trees in Baguio for its mall expansion and was linked to a violent demolition in Parañaque City that killed one resident; R-II Builders is involved in the plans to demolish more than 550 families in a parcel of land in Taguig City that they will rent out to businesses, R-II Builders’ Chairman Reghis Romero who also owns Harbour Centre Port Terminal, Inc. was linked to allowing slave-like conditions of dock workers in Manila Harbour Centre.

Local businessmen and politicians are likewise engaged in reclamation works, according to a review of government records, company websites, and multiple news reports.

Ramon See Ang

Atty Ruben D. Torres

Wilfredo Keng

Kitson S. Kho

Kenneth Gatchalian

Peter Suchianco

Francisco Tiu Laurel Jr

Reghis M. Romero II

Manny Pangilinan

Zhang Hongbo

Rogelio M. Florete

Carlos “Charlie” S. Gonzalez

Noli Arnulfo Igano

Jerry Sy

In Bacolod, the Bacolod Reclamation Gateway Corp. and Home Invest Realty Ventures owned by the family of Councilor Vladimir Gonzales will reclaim some portions of the Banago coast to build a housing project and commercial center, local officials say.

Silver Dragon Group owned by local businessman Jerry Sy also plans to reclaim a section of Banago’s coast reportedly for land development purposes.

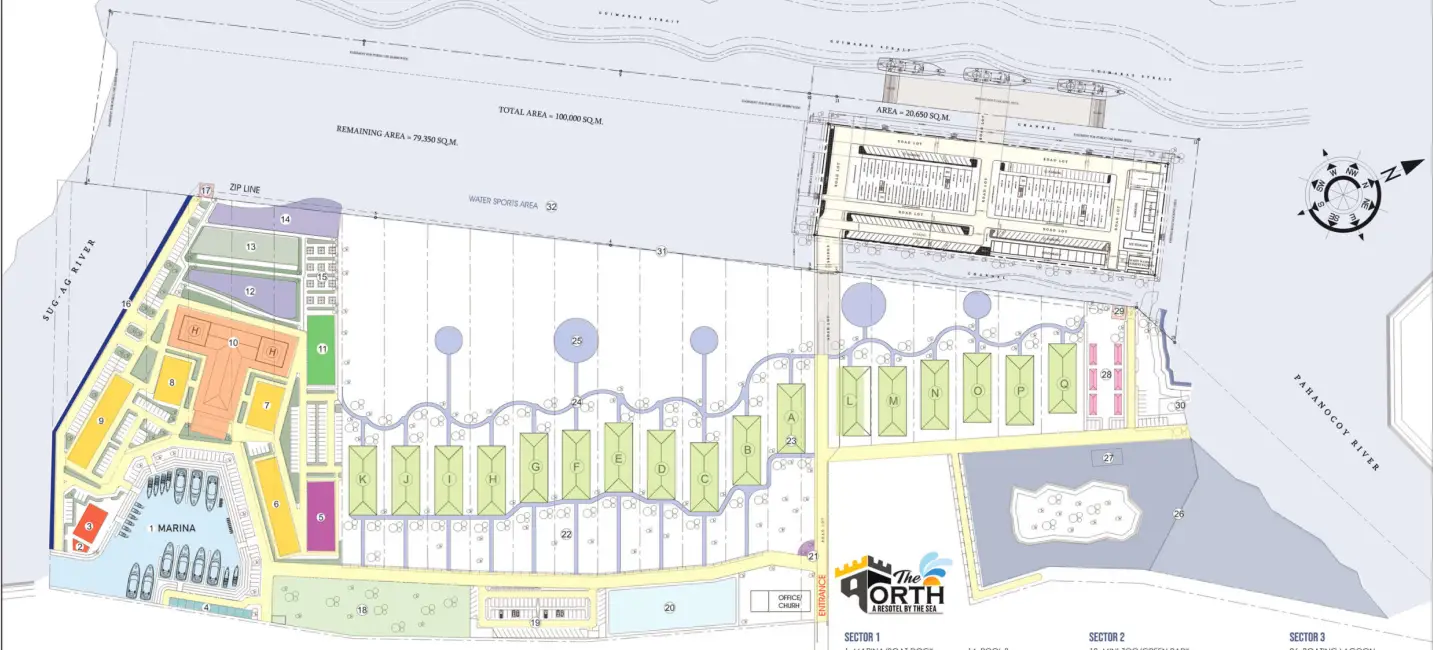

On the coast of Pahanocoy village, south of Bacolod, Tacolod Enterprises owned by Engr. Andres Tacolod is reclaiming land to expand his resort.

According to the think tank IBON Foundation, the ethics of conflict of interest in governance is already gone because the underlying subtext of running for politics in the country is that there is an interlocking interest to protect business.

“In the case of reclamation projects, policies are very strict and all reclamation projects are controversial that is why businesses need the support of the local and national government, and the local government willingly gives it. Why? Because of the big revenues that will come from reclamation projects,” explained Rosario Guzman, Executive Editor and head of the Research Department at IBON.

Guzman cited the controversial appointment of fishing tycoon Francisco Tiu Laurel Jr. as Department of Agriculture (DA) Secretary despite not having any background in agricultural development.

Tiu Laurel was president of Frabelle Fishing Corporation before he was appointed agriculture secretary and his company is the local government’s private partner in implementing the 320-hectare reclamation in Bacoor City. Aside from the Bacoor project, Frabelle has reclamation applications in Batangas and Cotabato City.

The agriculture secretary said that he has divested from the company in 2023.

The environmental risks of building on shifting sands

In 2021, the Bacolod City Legal Office, in response to complaints of residents and village officials, issued a cease-and-desist order against the reclamation works being done on the coast of Pahanocoy by Tacolod Enterprises. The resort area, now called The Forth, will be expanded to cover two additional hectares, according to the company’s website. The residents claimed that because Tacolod Enterprises weakened and changed the coastline by moving around huge quantities of sand, residents and their property were swept away in a subsequent typhoon.

According to residents, The Forth was built on a fishpond and coastal area that was dumped with sand. A portion of the Pahanocoy Creek that leads to the sea was also blocked.

In July 2023, when Super Typhoon Egay hit Negros Island, the Pahanocoy community experienced flooding so extreme it almost reached the ceilings of their homes. It was the first time in more than five decades that Erlinda Mahinay had lived in the village.

The 75-year-old could not recall a time when a flood that severe happened in the village of Pahanocoy. She couldn’t help but blame the reclamation and blocking of the creek for the incident that cost her some of her belongings and several chickens she was not able to bring along to the evacuation center.

"Sa una wala pa na gitambakan wala man gid mi, malunod. Pila ka bagyo ang undang nga bagyo, wala nag abot ang tubig diri. Jutay lang. Hangin lang ang among nahadlokan, wala tubig ya (When there was no dumping yet, we did not experience severe flooding. Several storms passed, one after another, but the water didn't reach here [neck deep], just a little. Only the wind bothered us. Just the wind. There was no water),"

Erlinda Mahinay, Pahanocoy resident

According to residents, reclamation works started in 2016 in the area where Tacolod’s had a 15-hectare Foreshore Lease Agreement (FLA) with the Department of Agriculture which was terminated in 2015. The reclaimed land is currently being leased to several resorts and another resort within a mangrove forest is being built.

Residents led by the Pahanocoy Against Reclamation Movement (PARM) also found that reclamation work adjacent to the resorts are ongoing. PARM had already filed a complaint with the local government and DENR, but Tacolod’s resort and reclamation activities continue. Altermidya sought the company for comment through their published contact details but has not received a response as of press time.

Erlinda Mahinay, 75 years old, points out how high the flood reached during Typhoon Egay (Doksuri) in 2023. She said that in the 50 years she’s lived in the village of Pahanocoy in Bacolod City, it was the first time she experienced a flood like that.

Photo by Chantal Eco

Sinking cities, ‘inconvenient truths’

Kelvin Rodolfo, a foremost expert in geology, has repeatedly warned the government against reclamation projects because of the danger it would bring to people living near the coastlines. Rodolfo is Professor Emeritus of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Illinois in Chicago

“So the problem is, they're making new land and it's crazy, instead of understanding that those are the worst places for people to be because of the waves and possible storm surge, they are risking the buildings and people’s lives,” he said.

In fact, a 2020 study conducted by Rodolfo with Rodrigo Eco of the University of the Philippines - Diliman and other scientists using satellite imagery shows that coastal areas with reclamation projects such as Manila, the CAMANAVA (Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas, Valenzuela) area, and Las Piñas City are sinking annually by 2.5 cm, 4.2 cm, and 1.8 cm, respectively.

“Land subsidence increases exposure to storm surges, tsunami, and flooding, tidal incursion, and potential decline in groundwater quality and availability in coastal communities. In areas with faults, ground fissures that emerged from fault reactivation threaten the structural integrity of buildings and structures built on top of them,” the study noted.

Eco, the lead researcher, pointed out that if infrastructures are built on top of reclaimed land, it will sink along with the dumped land just as is the case with Japan’s Kansai Airport.

“Due to ongoing land subsidence, infrastructures constructed on reclaimed land including people working and living in it face heightened vulnerability, this may also result in significantly escalated maintenance costs to mitigate sinking, rendering these projects dangerous and economically unsustainable,” Eco said.

Rodolfo said the findings are scientific truths but they are inconvenient truths which is why they are repeatedly ignored especially by the government.

“Greed, lust for money is what clouds people's judgment. So science, if it says that it's a bad idea, will be ignored because it gets in the way of making so many thousands (of) pesos per square meter or hectare,”

Kelvin Rodolfo, Geologist

Requirements and processes for the approval of reclamation projects are stringent as detailed by PRA’s Administrative Order 2007-2 and to get the required Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC) and Area Clearance from the DENR, project proponents need to submit an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and go through public hearings.

Project proponents whose projects have been approved have complied with the submissions and public hearings. But despite irreversible damages to ecosystems that have been identified in some EIA and there are clear oppositions to the projects–both from experts and residents, these factors seem to fall on deaf ears as is the case of the Bulacan Airport and Bacoor reclamation projects.

To monitor the environmental compliance of approved projects, a multi-partite monitoring team comprising representatives from relevant government agencies, project implementers, and civil society organizations must be established.

Altermidya requested EMB and PRA for reports from the monitoring team regarding ongoing reclamation projects that were issued with ECCs, but the request was denied.

Laarni Villamon’s family is among those who had to leave their home in Talaba II village for more than two decades to give way for the reclamation projects. They were given a house at a relocation site in Naic, Cavite, a one- to two-hour commute from Bacoor, but with no assurance yet if the property would be theirs. They also received a meager compensation of P10,000 from the local government. Another P30,000 coming from the DPWH was also promised but it has yet to be fulfilled.

But the Villamon family has not set down roots in Naic. They would only return to their new home once a month to feed their dogs and clean the house.

“We went back to Talaba II. We fished again because we had nothing to eat here. It's a nice house but we don't have any other livelihood here,” the mother of six said.

The Bacoor City government and PRA are supposed to provide a dormitory for fisherfolks near their fishing grounds, but Villamon said that they have no news if they will be able to avail of this facility.

Fisherfolk group Ang Pambansang Lakas ng Kilusang Mamamalakaya ng Pilipinas (Pamalakaya) documented more than 300 families that have already been displaced in Bacoor since 2021 while 400 more that have been threatened with eviction.

The number for the rest of the country would be much higher. The Villamons are among more than 25 million Filipinos residing in 143 cities and municipalities where reclamation plans are set.

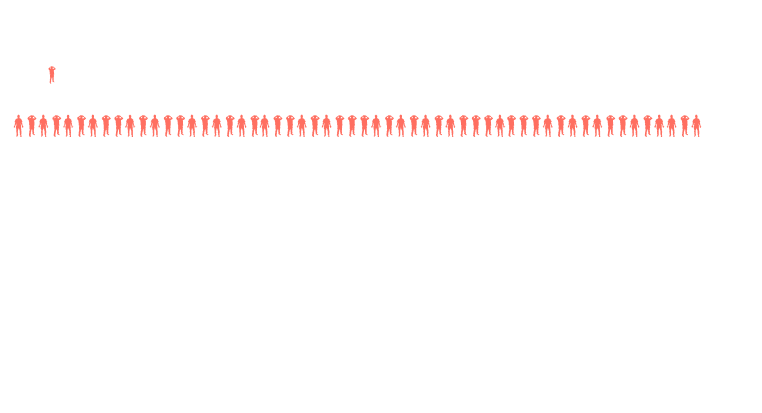

‘Up to one in seven Filipino fisherfolk affected by reclamation projects

Environmental advocates are convinced that while the government boasts of supposed economic gains from reclamation projects, that wealth is concentrated in the hands of investors, not local communities.

To Jordan Fronda, research and advocacy coordinator of the Center for Environmental Concerns, the reason why there are many reclamations is simply because many businessmen see reclamation as a profitable business. These projects will not generate sustainable industries that will help the Philippine economy, he added.

“Instead of making new islands that will house malls and casinos, our agriculture, fishing, and local manufacturing industries should be developed – that will generate sustainable jobs. They will not only help the development of Filipinos and the Philippines, they will also make Filipinos stronger, and make them more resilient to the effects of climate change,” Fronda said.

Of the two million registered municipal fisherfolk in the country, 14% or around 326,000 live in reclamation project sites. The estimate could be higher as not all fisherfolks have registered with the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources or their local government unit.

PRA Assistant General Manager Joseph John Literal told Altermidya that there would indeed be fishers that would be affected but he refuted that they would lose their livelihood.

"Ang effect lang talaga is they would just go a little bit farther… hindi naman majority ng Manila Bay ‘yung nare-reclaim natin. It's just a portion. So we're just talking of a difference in distance. But they can continue fishing (The effect really is they would just go a little bit farther... we're not reclaiming the majority of Manila Bay. It's just a portion. So we're just talking about a difference in distance. But they can continue fishing.),"

Joseph John Literal, PRA Assistant General Manager

While he acknowledges the possible impact on fish catch because of the disturbance caused by reclamation and construction works, he says it only happens during the project implementation.

“We're anticipating the time when this will be completed and we'll run the numbers again. So we can determine if it disappeared or just got misplaced," Literal said.

‘Final kill'

To many fishers, the effects are already apparent.

Bucado of Brgy. Banago in Bacolod City said he could harvest five to six kilos of lagaw or bisugo (mullet fish) every time he fished back in 2020. When 2023 entered, he could only haul in three kilos or five kilos if he’s lucky or if the fish are in season.

In Bacoor, Cavite, Ricardo Bagonggong, 64, operates a motorboat that he lends to fishermen and mussel divers. Already, he has seen a decrease in mussel harvest and the volume of fish caught in Manila Bay. But he also noticed that since the reclamation and dredging works commenced in the area, mussels are getting smaller or what they call bahong, which wholesalers do not buy.

“When I started harvesting mussels there, we would collect more or less 70 gallons in a single day. But now, in 2023, it's very few. Perhaps it may be only in my area but now if we get lucky we can collect 500 gallons during harvest season,”

Ricardo Bagonggong, motorboat operator

Bucado and Bagonggong live many miles apart, but their experience is similar. In some provinces with ongoing reclamation projects, there has been a noticeable drop in the fish catch in rivers, bays, municipal waters, and harvest in fish ponds.

In Cavite, where most of the mussels and oysters are harvested in Bacoor, harvest declined by 38% and 86% respectively in the past 10 years.

Meanwhile in Sorsogon where causeway projects are being constructed, mudcrab harvest declined from 866 metric tons 10 years ago to only 25 metric tons were harvested in 2023. That’s one crab caught for every 36 caught 10 years before.

In Gubat, Sorsogon, DPWH's coastal road/coastline protection project started in 2021 but residents protested and questioned the project that cut off several mangroves, displaced residents, and affected mudcrabs harvest in the area. The project was halted in 2022 through a cease-and-desist order due to the lack of ECC.

Related story here: Gubat Bay sa Sorsogon, planong tayuan ng coastal road

According to Pamalakaya, the fishing industry has already been in decline for several years due to various factors, from overfishing, industrial and human waste pollution, fishpond pollution to mining silts and oil spills.

CEC’s Fronda explains that a lot of life or biodiversity is lost or destroyed every time reclamation is carried out. Fish, corals, mangroves, those that crawl under the sea, in the sand, lose habitat, hence the numbers decrease. They can also move away from the habitat, from just near the shore and into the deeper parts of the sea, so it is also difficult for fishermen to catch fish.

“The damages that reclamation projects will cause are massive and irreversible and no amount of rehabilitation can return coastal areas to their original state. Because of this, the biodiversity becomes weak, making the people more vulnerable,” he added.

To Hicap, reclamation projects are the final kill to the local fishing industry. “If it has been gasping for breath, somehow surviving, this is what took its final breath,” he said.

Pamalakaya claims that fish catch and other marine stocks are deteriorating, drastically affecting the livelihood of fisherfolk. They estimate that fisherfolk continue to lose 80% of their daily income because of the environmental damages inflicted by reclamation.

Concerned government agencies including DENR and BFAR have long before recognized that reclamation works will result in “permanent decreases in localised fish catch” as articulated in the government’s coastal management guide. Despite this, government policies continue to pave the way for these reclamation projects.

The PRA recognized that there is no monitoring of whether fish catch is affected by these dump-and-fill activities.

“Yung numbers kasi even before the reclamation may decline. Bumaba ba talaga? I don't know because ang experience namin dun even dito sa Cavite may mga big business fishing pa rin…but we cannot say what really affected the decline. (Even before the reclamation, the numbers show that there is decline. Did they really decrease? I don't know because our experience there, even here in Cavite, there are still big businesses fishing…but we cannot say what really affected the decline.),” said PRA’s Literal.

Bucado and his wife, who has no other source of income, said that their family, especially since some of their children are still dependent on them, will go hungry if reclamation works continue in their fishing grounds in Banago.

“Kung wala kami sang kwarta, mangisda kami para may makaon kami… Ang among panabuhian ari lang gid sa dagat, amo man lang ni ang nabal-an namon sa pila katuig. Kung madula ang dagat, ano matabo sa amon (If we don’t have money, we just go out to fish so we can have something to eat. We only rely on the sea for our everyday food and other needs. This is the only work that we’ve had for several years. If we lose the sea, what will happen to us?” the fisher said.